This is a critical time for investors and policymakers alike.

Geopolitical tensions, elevated market volatility, and the fastest pace of central bank tightening in decades are meaningful economic headwinds contributing to an unusually uncertain environment. We discussed these and other factors at length at our Cyclical Forum in September in Newport Beach.

We concluded that a recession is likely to strike across developed markets and that elevated inflation is likely to stick around. Central banks are in a miserable position, having to address inflation while growth is already at risk.

We see this as a time for caution and flexibility in portfolios, and yet higher yields are adding to the attractiveness of bonds. Investors can potentially earn higher income while pursuing resilience amid market volatility. We discuss the case for bonds – and review other assets – in the investment implications, further below.

As we worked toward these and other conclusions, we reminded ourselves of the concept of radical uncertainty, where uncertainty can’t be quantified by statistical distributions or probability-weighted average outcomes, but rather is unmeasurable and represents unknowable unknowns. As a result, although we discussed point forecasts for growth and inflation, we agreed that the range of possible outcomes was particularly wide.

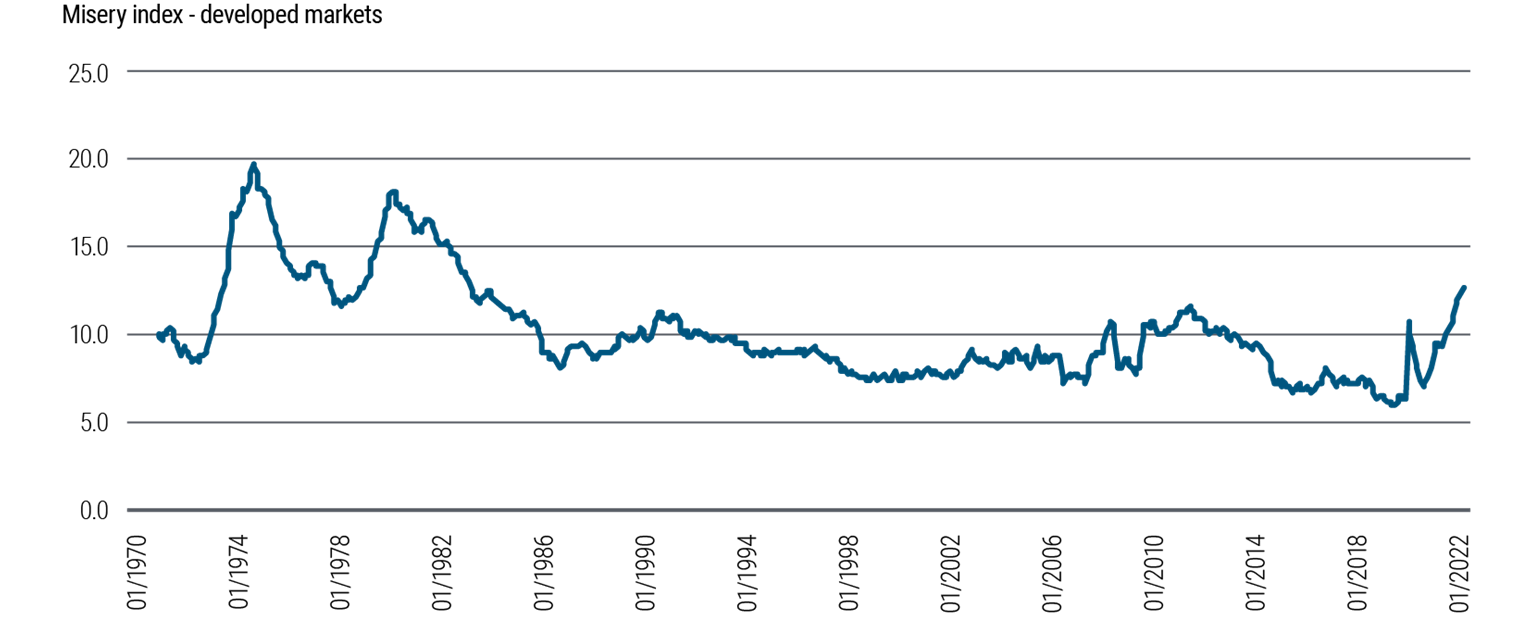

However, one thing we feel certain about: Borrowing from Arthur Okun’s misery index (created in the 1960s), which adds up inflation and unemployment rates to characterize economic performance, misery is increasing for central banks and policymakers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Macro misery (combined inflation and unemployment) in developed markets at highest levels since 1980s

Initial conditions

To understand what this misery could mean for economies, markets, and investors, it’s useful to remind ourselves of the initial conditions and recent developments since our last Cyclical Forum in March. The war in Ukraine had just started, and although the outlook was highly uncertain we crafted five key takeaways for the road ahead. First, the war was an “anti-Goldilocks” economic shock, whereby accelerating inflation would be accompanied by slower (or even negative) real GDP growth. Second, given the impact on supply chains, non-linear growth and inflation responses were likely. Third, the relative dependence of the European Union (EU) on Russian energy would likely beget greater economic divergence across regions. Fourth, financial conditions would tighten, as central banks would likely focus on fighting inflation over supporting growth. And fifth, with inflation and government debt already elevated as a result of the pandemic, the fiscal response to the shock would likely be limited. (See our March 2022 Cyclical Outlook: “Anti-Goldilocks.”)

Since then, macro developments have generally evolved along these lines. However, the shocks have been much more pronounced in several key ways: Economic disruptions from the war have intensified. Western sanctions and the Russian response to limit and more recently halt gas flows through various pipelines to Europe will likely have material economic consequences. Inflationary pressures appear more entrenched, not only in the U.S. but across regions. And central banks’ focus on fighting inflation has produced much more significant tightening in financial conditions than anticipated, which has been most pronounced in the U.S. due to the dollar’s strength.

There have also been some unanticipated events since March. Chinese growth unexpectedly stalled, as stop-start COVID-19 lockdowns and a piecemeal approach to policy easing weighed on activity. And fiscal policies across regions are now more divergent, with the U.K. and Euro area implementing greater demand-boosting support. Indeed, efforts to cushion the impact of higher energy prices on consumers and businesses have become the top political priority for these governments. In the U.K., a large fiscal package was announced in late September that, among other things, would cut taxes across the board and cap energy costs for households, amounting to roughly 4%–5% of GDP in the first year alone. Meanwhile, various countries within the Euro area have also moved to expand government spending in the form of energy caps, fiscal transfers, and subsidies in an effort to blunt the negative effects on discretionary incomes of higher energy costs. Most recently, the German government proposed a mechanism to cap energy prices, which is estimated to cost 5% of GDP. However, to be sure, the aggregate Euro-area-wide spending amounts still appear nowhere near the size of what is being proposed in the U.K.

Outlook: Mounting macro misery

These developments will affect the global economy with a lag, and we see three crucial implications for the outlook over the next six to 12 months:

1) Recession more likely than not; unemployment poised to rise

Recession and rising unemployment rates across large developed markets (DMs), especially the Euro area and U.K., appear quite likely despite further government efforts to support their economies.

The geopolitical tumult has compelled Russia to greatly reduce and even halt gas flows through various pipelines into Europe – the major source of European energy imports. Although the Euro area has responded with non-mandatory rationing schemes, greater gas imports from the rest of the world, and fiscal measures to distribute the burden, Europeans still face record gas prices (and the threat of mandatory rationing in the event of a colder than normal winter), which in turn would reduce discretionary real incomes, render much factory activity uneconomical, and raise costs across global supply chains.

While the direct trade linkages from Russia to other large non-European markets are more limited, disruption will likely spill over to the U.K., U.S., and other DMs as European industrial production and trade flows are impaired. The U.K. appears particularly vulnerable, despite fiscal stimulus focused on shielding households from higher energy costs, due to its strong trade ties with Europe and a more general dependence on imported power and electricity.

As we’ve learned from the pandemic, a shortage of small value-added components can have large effects.

Meanwhile, U.S. real GDP will also likely experience a period of modest contraction that pushes the unemployment rate above some estimates for NAIRU (the nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment, which is around 4%, according to the Congressional Budget Office). Robust domestic energy production helps insulate the U.S. from the power scarcity crisis in Europe and the U.K. Nevertheless, impaired European trade flows and supply chain disruptions are a stagflationary shock that will probably hinder the U.S. economy at a time when it is also dealing with some of the fastest tightening in financial conditions since the 2008 financial crisis, generally low consumer and business sentiment, and elevated uncertainty, all raising the risk of a harder landing for the U.S. economy. While only 3% of the inputs into overall goods and services consumed in the U.S. are sourced in Europe (according to trade in value-added data from the OECD as of February 2021), the pandemic has demonstrated how a shortage of small value-added components can have large effects on supply chains. Vulnerabilities in the German chemical industry, which is an important input into a range of products including fertilizers, industrial parts, and automobiles, is particularly worrisome. The combination of these shocks is expected to weigh on corporate profitability, limit investment, and ultimately result in a higher U.S. unemployment rate.

Finally, while we don’t expect a recession in China, we do see downside risks to real growth emanating from the country’s zero-COVID policy and property sector recession. Falling exports to the U.S., Europe, and other developed economies will likely also be a strong headwind for China’s policymakers as they try to maintain their growth targets, despite some rising trade with Russia.

Despite this challenging outlook, our baseline view is for relatively shallow recessions across the major DMs given that 1) household and private sector balance sheets have remained strong, on average, 2) debt constraints become less binding in inflationary environments, and 3) to date, the rapid tightening in financial conditions hasn’t yet resulted in widespread bank funding market stress. Nevertheless, recent global financial conditions tightening on the back of the fiscal announcements in the U.K. has served as a reminder of the linkages between real economies and financial markets, and the risks of a financial market accident resulting in more severe recessions across large DMs.

2) Inflation is sticky

Core inflation rates that are above central bank targets now appear more entrenched, and although headline inflation is still likely to eventually moderate meaningfully over our cyclical horizon, it now looks likely to take more time.

Consumers will likely feel the sting of elevated power and electricity prices to varying degrees across the Euro area and U.K. as governments look to mitigate and even cap the pass-through of wholesale prices to end users. Easing global crude oil prices should help ease headline inflation elsewhere, including in the U.S., Canada, and Australia. To be sure, we forecast headline inflation moderating notably in most regions over our cyclical horizon. However, part of that expected moderation is due to a technical assumption: We use energy futures curves to forecast energy inflation. Like most other things, the outlook for global energy prices seems more uncertain than usual as DM recessions could collide with supply constraints emanating not only from the war in Ukraine, but also the global transition from brown to green energy sources.

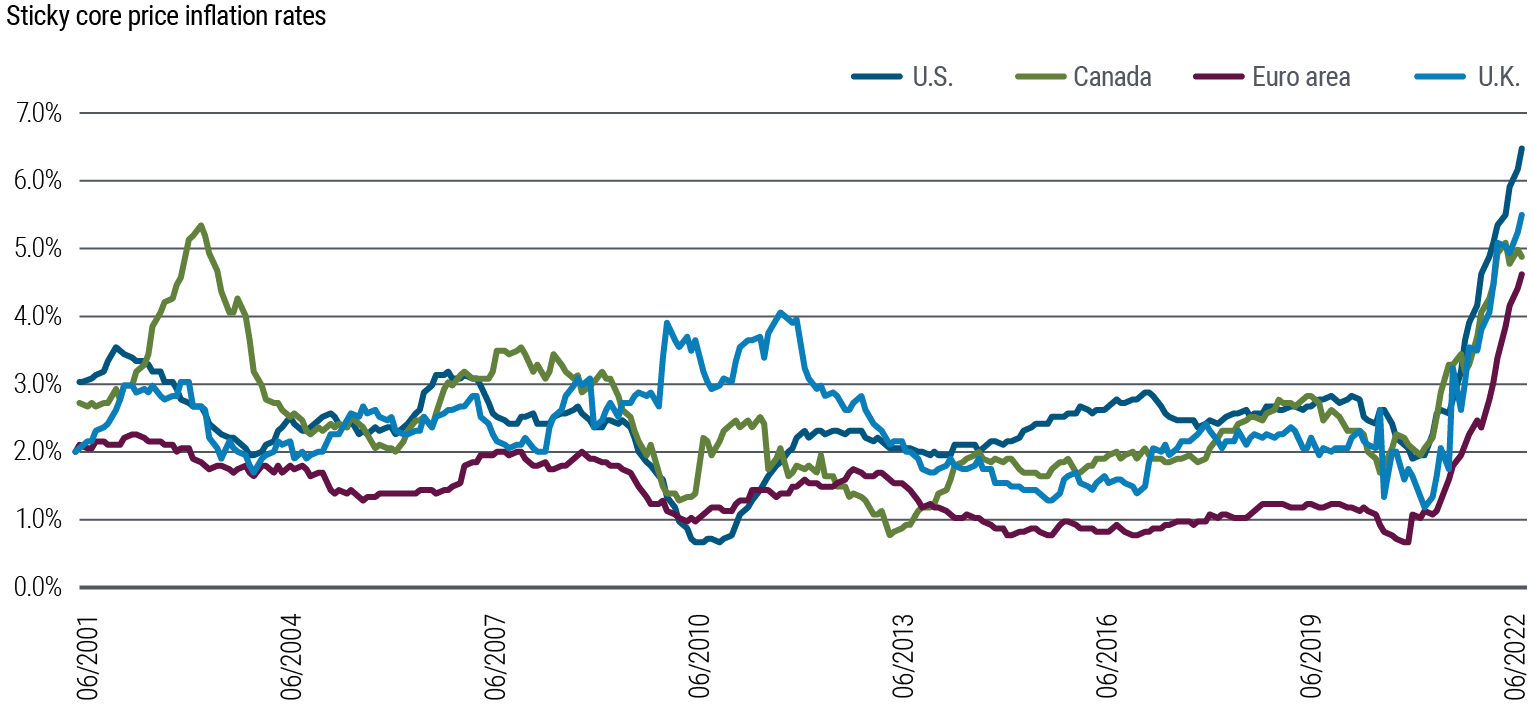

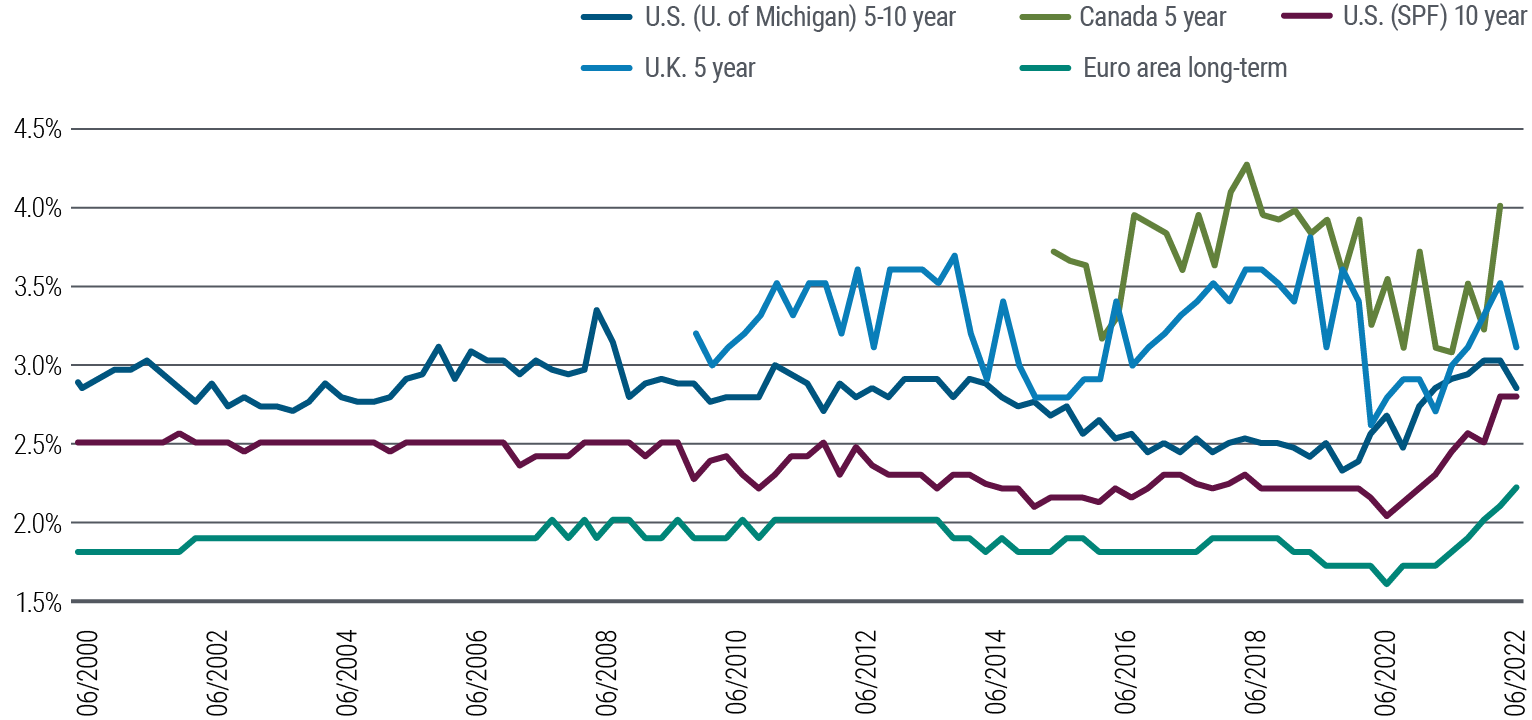

More important in our view, elevated core inflation is starting to appear more entrenched. Rising inflation has broadened beyond categories affected by pandemic-related global goods production disruptions to include components of the price basket that tend to be more cyclical, including shelter and services. Indeed, measures of “sticky” inflation have generally accelerated across major DMs, with the acceleration in the U.S. being the most pronounced (see Figure 2). Furthermore, measures of longer-term inflation expectations have been trending generally higher over the past two years (see Figure 3), while tight labor markets have pushed up wages. This is especially true in the U.S., where wage pressures have broadened from the low-wage, low-skill service sectors to a range of industries, occupations, and skill levels.

While our baseline sees core inflation taking more time to subside than central banks had recently hoped, downside risks to the real growth outlook also point to higher-than-usual inflation uncertainty, and a non-remote possibility of a more dramatic disinflationary bust.

Figure 2: Core inflation has become considerably more entrenched, or sticky, in several developed markets

Figure 3: Long-term inflation expectations have been trending generally higher

Perhaps most concerning for central banks, high and rising inflation has occurred against a backdrop of secular efforts to build supply chain resiliency and transition to green energy sources (see our June 2022 Secular Outlook: “Reaching for Resilience”). Eventually, higher prices should provide a strong incentive to innovate, but the cyclical implications of these secular developments are higher costs that tend to keep consumer price inflation from returning to lower, pre-pandemic levels.

3) Monetary policy: Tighter for longer

The combination of higher unemployment and stubbornly above-target inflation has put central bankers in a tough spot, but their overall actions to date suggest they are squarely focused on bringing inflation down. The risk of higher inflation contributing to rising inflation expectations and so on appears more acute in the context of inflationary trends that are broader than just pandemic-related supply shocks. And with inflation now broadening, it is much less clear that inflation will moderate on its own without additional monetary tightening to bring real interest rates above their neutral levels. To date, real interest rates have remained low, despite generally tighter financial conditions, arguing for further nominal rate hikes.

The European Central Bank (ECB) is likely to face the toughest trade-off between employment and inflation, although officially it has a single, price-stability mandate. Of the major economies, the Euro area is the most affected by the fallout from the war in Ukraine and the sanctions on Russia, and it is likely to suffer the largest GDP contraction. However, because Western sanctions (and Russian energy supply outages) aren’t likely to be reversed anytime soon, the ECB will likely need to position monetary policy with an eye toward restricting demand in the face of these new supply constraints. To be sure, European estimates of the real neutral interest rate put it well below other developed markets’ rates, suggesting the ECB has less work to do to move to a restrictive monetary policy stance.

The Federal Reserve, the Bank of England (BOE), the Bank of Canada (BOC), and other DM central banks face a similar trade-off. However, with inflation running well above long-run targets, further rate hikes are likely appropriate as policymakers seek to achieve a restrictive stance – especially in the U.K., where we expect the BOE to position monetary policy to offset the recent fiscal actions – before holding rates there until inflation has moderated meaningfully back toward target. In the U.S., we expect the Fed will raise its policy rate to a range of 4.5%–5% and then pause to assess the impact on the economy of its tightening (recognizing that monetary policy affects the economy with long and variable lags).

How high DM policy rates ultimately rise to provide sufficiently restrictive financial conditions will depend on the sensitivity of the respective economies to interest rates. Judging by recent housing market performance, central banks of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand may reach a point where they pause before the U.S. and especially the U.K. In the U.K., as a result of the announced fiscal expansion, the ultimate destination of the BOE’s policy rate could be well above that of other DM central banks, despite the BOE’s recent shift from shrinking its balance sheet to once again expanding it in an effort to mitigate the systemic risks to the U.K. pension system from the swift adjustment in longer-term interest rates.

With inflation running well above long-run targets, further rate hikes are likely appropriate as policymakers seek to achieve a restrictive stance.

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) is the one exception to this outlook, since inflation in Japan has thus far remained surprisingly muted. If Japan’s inflation dynamics eventually follow in the footsteps of their international peers, we expect the BOJ to adjust policy accordingly. However, for now, with wage pressures still muted, the BOJ is likely to remain focused on anchoring Japanese inflation expectations, which have adapted to the country’s persistently below-target inflation over the years.

Needless to say, this outlook for monetary policy also raises the risk of a hard landing. While our baseline includes a shallow recession, the risks of financial market accidents or sudden stops in debt markets will tend to be elevated in an environment where central banks, using blunt interest rate and balance sheet tools, have to slow demand. These second-round effects are difficult to forecast ex ante, as systematic financial market linkages only become obvious with a lag when markets are already under stress.

The next recession: Shallow but longer

While our baseline forecast is for shallow recessions across DM, we also don’t expect growth to quickly bounce back to an above-trend pace. With inflation running well above central bank targets, and post-pandemic fiscal deficits and debt now significantly higher, the fiscal policy response to falling activity is also likely to be more muted, producing a growth outlook that remains sluggish and below-trend for some time after the period of contraction. The misery index, even when it peaks, may take some time to reach a more comfortable level, as lower inflation is offset by higher unemployment.

While we do expect fiscal easing in Europe and the U.K. to cushion their economies amid recession, it likely won’t be enough to avoid recession given central banks’ likely response to the additional inflationary pressures, nor will it be likely to lift growth back above trend thereafter. Meanwhile, in the U.S., only minor additional fiscal support looks probable in the near term given bipartisan concerns about elevated inflation.

While this fiscal outlook, coupled with tight central bank policy, is not great news for cyclical growth, it’s likely exactly what is needed to conquer inflation. The pandemic episode illustrated clearly that inflation is not only a monetary but also a fiscal phenomenon.