Over the past few months, economic recoveries have been uneven across regions and sectors. In the case of the U.S., this has contributed to supply chain bottlenecks and a bump up in inflation. Nonetheless, at PIMCO we continue to view the factors driving the recent price surge as transitory and, as a result, haven’t materially changed our broader views on the impact of the pandemic, policy, or economic growth since our March Cyclical Outlook.

So far, the market reaction to these macro developments has been generally muted, and despite higher inflation risks, the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note has declined 25 basis points since mid-March. However, as we discussed at our Cyclical Forum in March, we see risks that greater macro uncertainty and volatility translate into a similar increase in volatility across asset markets. As a result, we believe it makes sense to be patient at a time of more limited high conviction opportunities and generally rich valuations, and to focus on maintaining liquidity and flexibility in our portfolios. If markets overshoot, as they tend to do, we want to have the flexibility to take advantage of these opportunities.

Economic outlook: peak pandemic, peak policy, peak growth

Over the last several months, public health data have indicated that the global pandemic, measured by number of cases, likely has peaked in the second quarter of 2021. The seven-day rate of new cases of COVID-19 globally declined from around 5.8 million per week in mid-April to 2.9 million in early June. At the same time, despite a bumpy start, vaccination rates across developed markets (DM) have accelerated, and DM countries are now projected to reach herd immunity over the next several months. As a result, global rates of new cases and deaths are likely to continue to decline, despite slower vaccination rates in emerging markets (EM) countries.

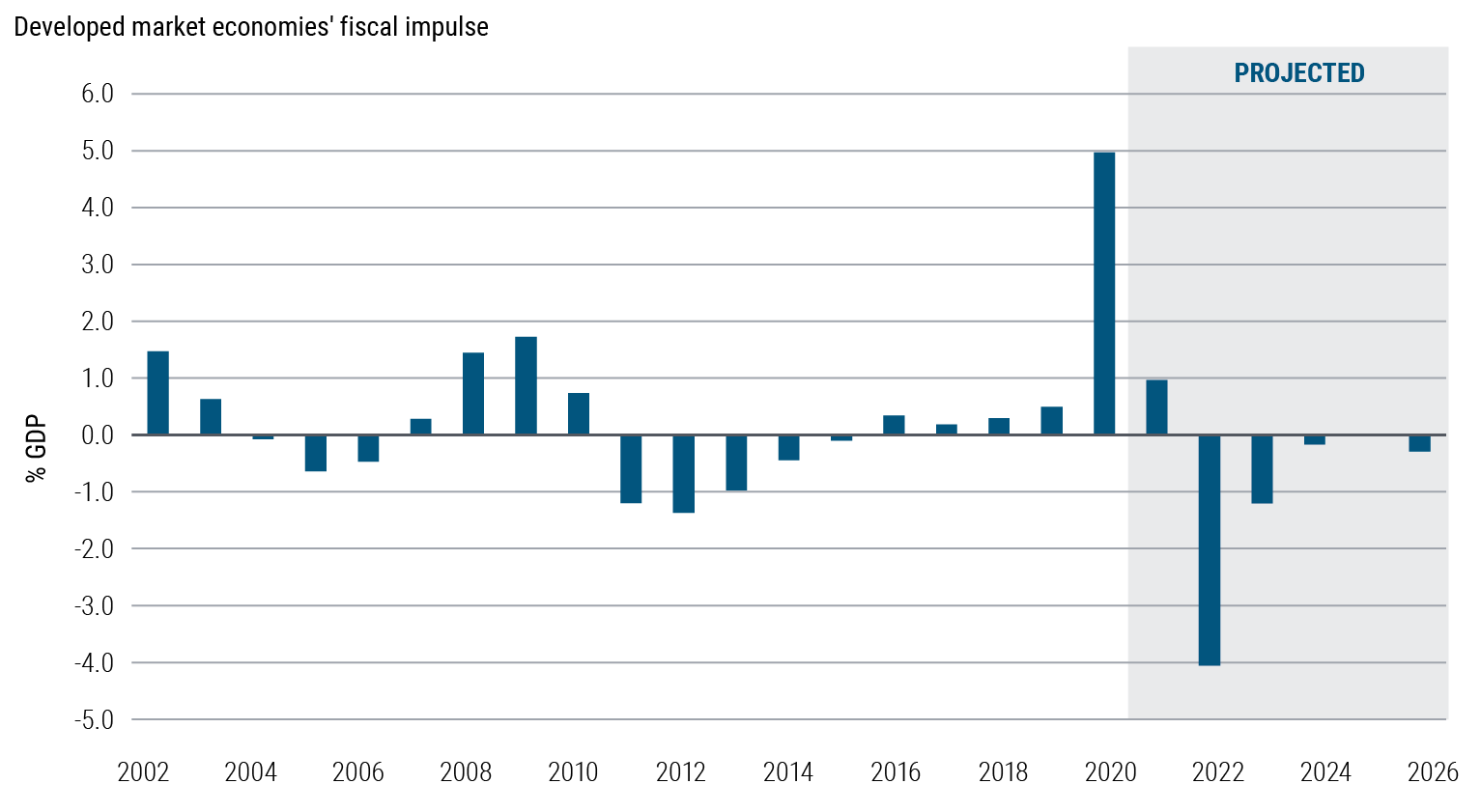

However, with the pandemic receding, policy support has also likely peaked. Within DM, the fiscal impulse, or the change in structural government deficits, is now waning, and will turn into an outright drag on growth in the months ahead (see Figure 1). We believe this will occur despite any new U.S. infrastructure spending. The additional pandemic relief legislation passed in March 2021 boosted the U.S. economy, with positive spillovers to the rest of the world. However, the U.S. household stimulus checks, which largely drove the DM fiscal impulse in 1Q 2021, won’t repeat, and the federal government’s enhanced unemployment benefits are expected to fully expire by the end of 3Q.

Figure 1: After peaking in 2020, fiscal policy support could exert a drag on developed market economic growth over the cyclical horizon

Similarly, tighter financial conditions in China have slowed credit growth in one of the world’s major economic engines, while developed market central banks have started to slowly shift direction, either by taking the first step toward policy normalization (e.g., the Bank of Canada and Bank of England tapering asset purchases) or signaling plans to do so (e.g., the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) indicating it discussed tapering at the June meeting).

These factors will tend to impact growth to varying degrees across industries and across regions, and will likely result in a somewhat desynchronized DM growth rebound in 2021. However, we expect the rebound will give way to a synchronized growth moderation in 2022, albeit to a still strong, above-trend pace. In particular, after the recession and partial retracement in economic output in 2020, we believe the U.S., U.K., Canada, and China likely achieved peak growth for 2021 in the second quarter, while the EU and Japan will likely peak in the third and fourth quarters, respectively.

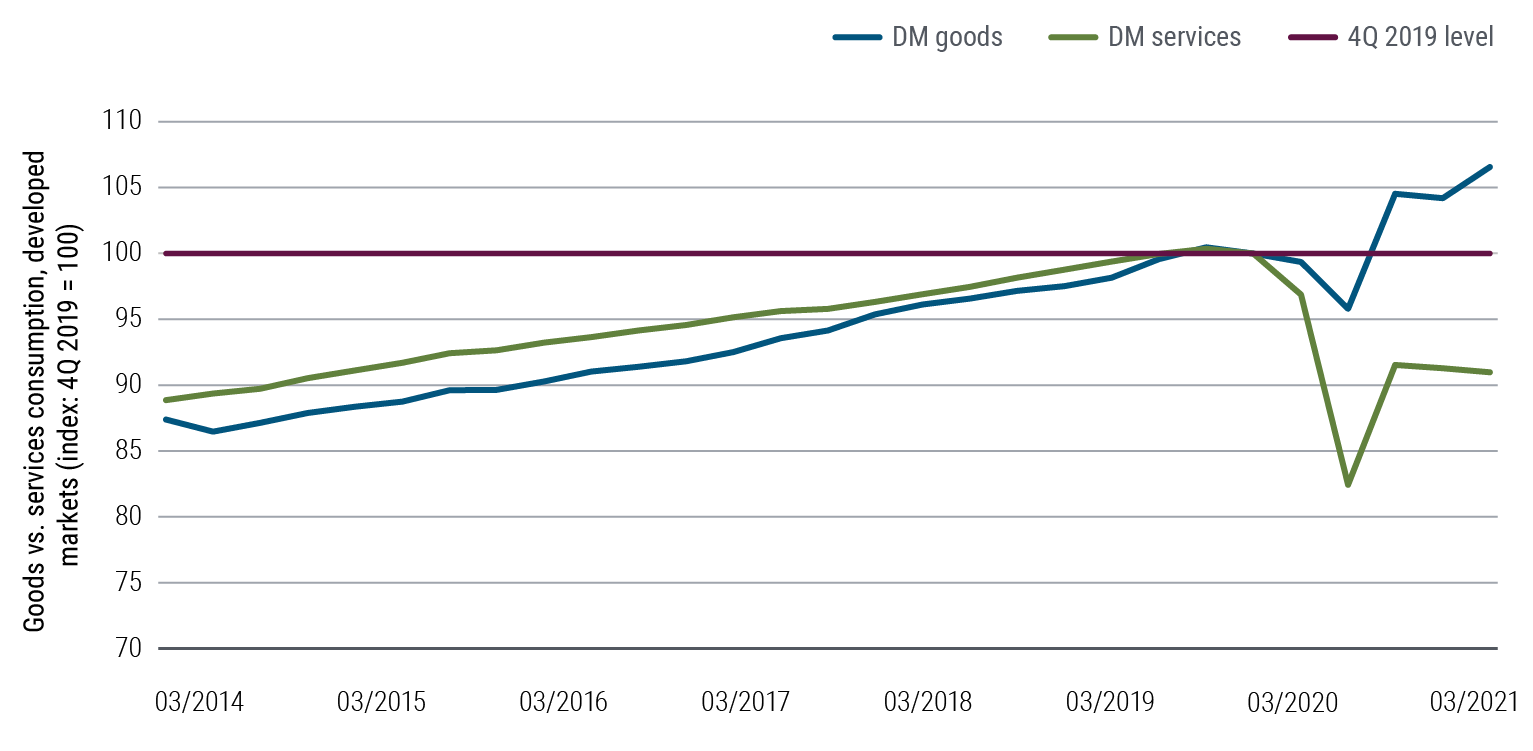

On a sector basis, peak demand growth for consumer goods will also likely give way to a reacceleration in services spending. While many aspects of the COVID-related recession have been unique, the absence of a contraction in consumer goods demand has been particularly notable. Across DM countries, consumers generally substituted durable goods purchases for services (see Figure 2). For example, U.S. sales of exercise bikes exploded while spending on fitness center memberships plummeted. Similarly, demand for autos accelerated as public transportation declined. There are many more examples. However, while the above-trend pace of goods consumption was an important contributor to the overall recovery in DM in the second half 2020 and the first half of 2021, this growth will also likely peak in the second or third quarter of this year, as the pandemic fades (it is hoped) and consumer preferences shift back toward services spending.

Figure 2: Since the pandemic began, goods consumption has far outpaced services consumption in developed markets – but that trend could shift later in 2021

Overall, we expect DM real GDP will grow 6% in 2021 (measured by 4Q over 4Q) and moderate to below 3% in 2022. Meanwhile, slower vaccination rates especially in the EM countries will likely delay a fuller recovery relative to DM. We expect EM GDP growth to accelerate up to 5% in 2022 (4Q/4Q), after growing 3.5% in 2021.

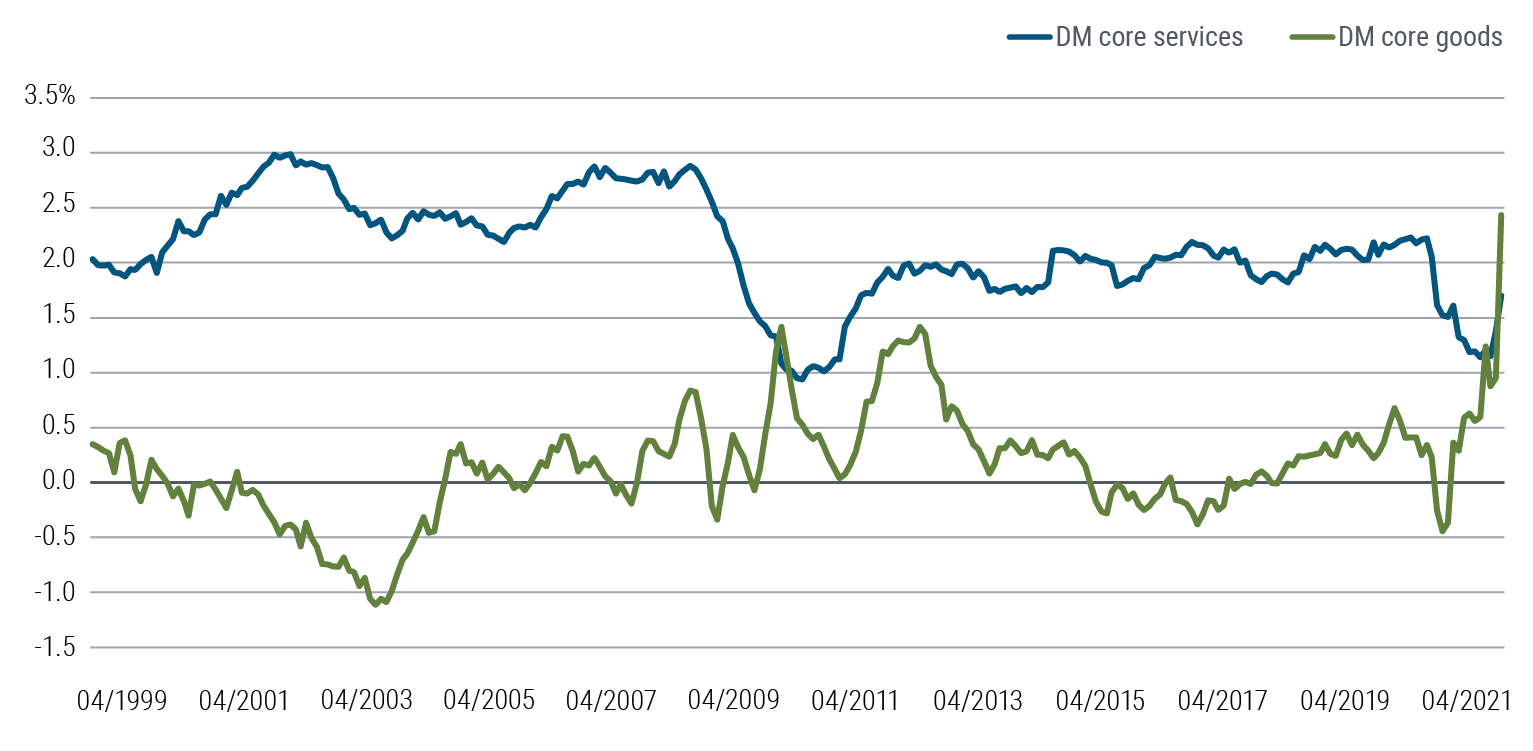

Inflation: a spike but not a spiral

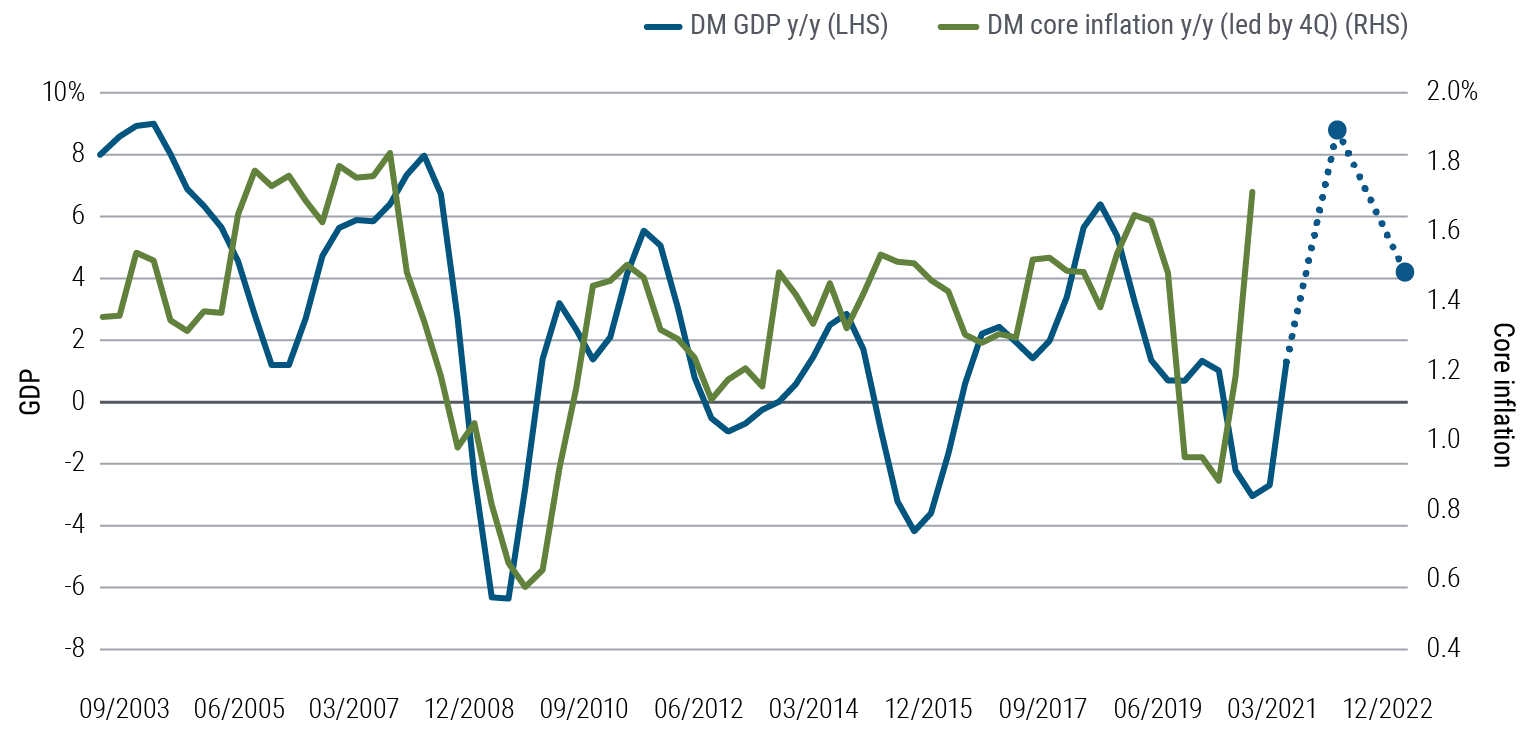

Since DM inflation generally lags DM growth, we also project inflation to peak in the coming months (see Figure 3). However, the exact timing and magnitude is more uncertain due to supply constraints, which have had a larger-than-anticipated impact on realized goods inflation. As of April 2021, core DM inflation at 1.7% (year-over-year or y/y) had fully recovered from its pandemic dip; however, the composition of the inflationary pressures was quite different. Indeed, while services inflation was still well below its pre-pandemic level, goods inflation was well above (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: With developed market GDP growth peaking, the inflation peak may not be far behind

Figure 4: Core inflation has been largely driven by goods prices amid the pandemic

Looking closely at the data, the acceleration in goods inflation in developed markets was largely driven by the skyrocketing prices of U.S. used autos. The global shortage of semiconductors has hindered U.S. production of new cars more so than in other developed markets. The price effects of the shortages are evident chiefly in the used car market, in large part due to U.S. rental car companies resorting to used cars to rebuild fleets after liquidations last year. Logistical bottlenecks have also plagued the U.S. goods market: West Coast port congestion and a dearth of truck drivers have lengthened delivery times and increased costs, which are being passed on to consumers.

Nonetheless, these supply constraints are expected to ease in 2022, and this coupled with peaking goods demand will likely moderate inflation in the second half of 2021. Furthermore, with the unemployment rate at 5.8%, the U.S. is still quite a ways from full employment. The labor situation along with a relatively flat Phillips curve (suggesting the statistical relationship between employment and inflation is less significant), still-anchored inflation expectations, and accelerating productivity growth make the risk of spiraling U.S. inflation seem remote.

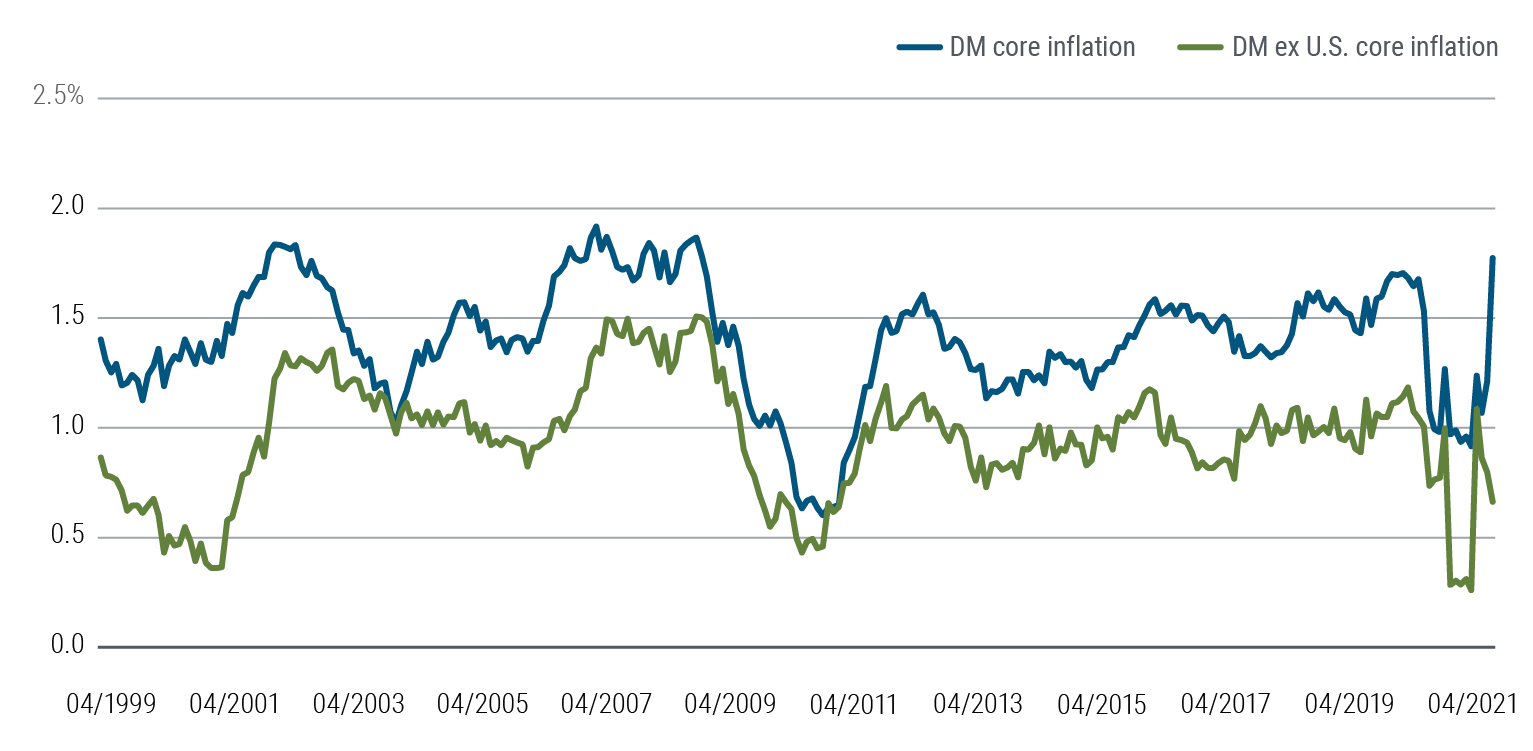

Outside of the U.S., underlying inflationary pressures in other developed markets have been much more subdued. Indeed, as of April 2021, DM core inflation excluding the U.S. was running around 0.6% y/y versus 3.0% core U.S. inflation (see Figure 5). This divergence has occurred despite the global nature of the supply chain bottlenecks, because fiscally stimulated demand for goods in the U.S. has also outpaced other developed markets. However, the fact that the large fiscal transfers aren’t likely to repeat and U.S. fiscal policy will turn to a drag on growth in 2022 argues for inflation to also moderate in 2022.

Figure 5: U.S. is primary driver of developed market core inflation

Overall, we forecast DM inflation to end 2021 running at a 3% average annual pace, before moderating back to 1.5% in 2022 – below DM central bank targets. For the U.S., we expect the y/y rate of core inflation to peak in 2Q 2021 around 4%, and end the year at 3.5%, before moderating back to 2.3% in 2022.

Policy handoff doesn’t come without risks

Our base case for growth and inflation has both downside and upside risks. The handoff from policy-induced growth to organic growth could be better than expected … or it could be worse. Upside risks include 1) a large accumulation of excess household savings that fuels a more pronounced consumption boom (while likely contributing to higher inflation), 2) an elevated pace of innovations and higher productivity growth that supports corporate profits and real wages, or 3) generally easy financial conditions that continue to support lending and capital formation.

On the other hand, downside risks to the baseline outlook include 1) higher inflation that squeezes corporate margins and erodes real household incomes, 2) economic reallocation that takes a long time and results in elevated levels of long-term unemployment, or 3) more permanent changes in post-pandemic household preferences toward savings and consumption.

Central banks stay the course

Since March 2021, many major DM central banks started to gradually shift the stance of monetary policy. The Bank of Canada (BOC) and Bank of England (BOE) took the first steps toward policy normalization by tapering their bond purchases, while the Federal Reserve indicated that at the June meeting it started discussing plans to wind down its purchase programs.

Major developed country central banks are unlikely to hike rates over the cyclical horizon

Turning to the outlook, we continue to expect the Fed to initiate a gradual tapering of its monthly asset purchase pace later in 2021, and to end the purchases by 3Q 2022. Regarding the announcement timing, we continue to view the December Fed meeting as most likely; however, we wouldn’t rule out an announcement as early as September. Although the current U.S. inflation spike is likely to be transitory, the Fed may want to manage the risk of an unwanted acceleration in inflation expectations by bringing forward its tapering plans modestly. This would also give the Fed the option to further adjust its outlook for policy rate hikes in the event higher U.S. inflation does prove to be more persistent.

Conversely, we think it’s likely that the ECB continues purchasing assets (also known as quantitative easing or QE) through our cyclical horizon. While it is possible that small adjustments are made to the ECB purchase programs, we see a low likelihood that the ECB will meet its inflation objective by 2022. Therefore, implementing a clear path and strategy for ending purchases is likely a question for the ECB over our secular (not cyclical) horizon.

Finally, notwithstanding the expected changes to DM central banks’ QE programs, we don’t expect DM central banks to begin hiking policy rates over our cyclical horizon. Indeed, the central banks in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia are likely to lead with the first hikes in 1H 2023, followed by the Fed and BOE in 2H 2023, in our view. The ECB, which has had more difficulty in meeting its 2% inflation target over the last decade, isn’t expected to hike until much later, while the Bank of Japan continues to struggle with deflationary trends.